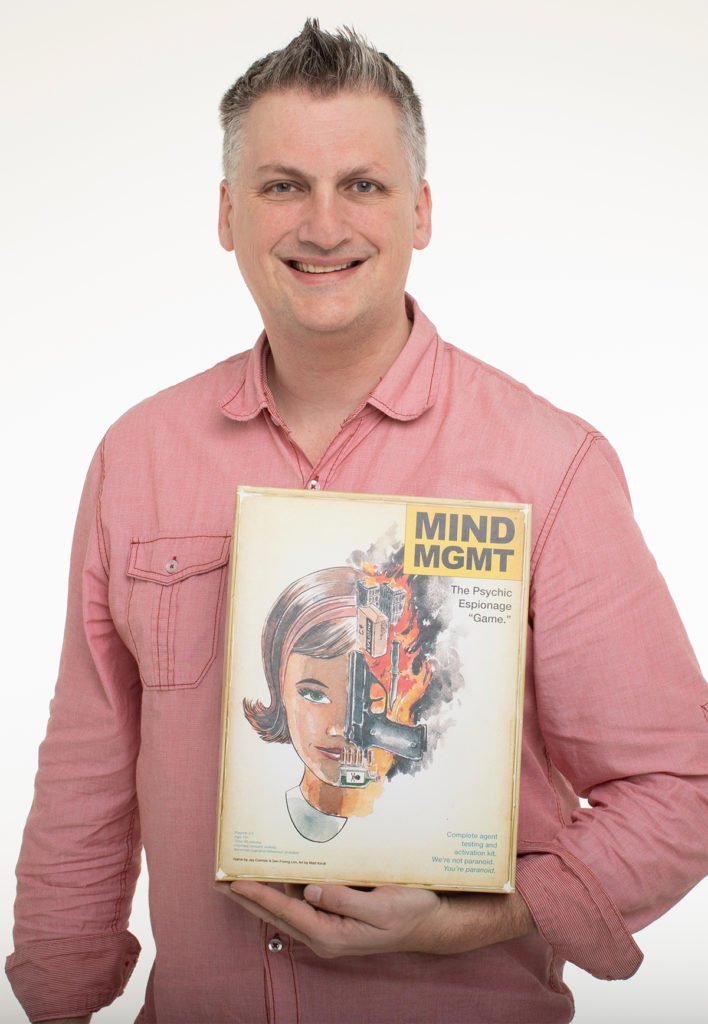

Jay Cormier is a board game designer with more than a dozen published games such as Belfort, Tortuga and the critically acclaimed, Junk Art, under his belt. I had the wonderful opportunity to chat with him on his game designing journey and his recent play-testing journal Kickstarter project.

EL: Tell us a little more about yourself and how you got yourself into the hobby and eventually into game designing.

JC: I’ve definitely been gaming my whole life. I remember always enjoying family game night — even if it was Trivial Pursuit! I played D&D with my friends and I even remember making games for my friends to play back then. Fast forward to the 90s when my friend, Sen-Foong Lim introduces me to Magic: The Gathering. I was instantly hooked and couldn’t get enough of it. I spent a lot of money on this thing!! From there Sen and I started to play other games like Robo-Rally, Settlers of Catan, Supremacy and more. We loved playing games! Then fast forward to the early 2000’s and Sen and I thought we could make a board game too since we’re both creative and kinda smart. So we tried….but failed miserably. We knew what a good game looked like and played like, and this wasn’t it. So we gave up and never talked about it again. In 2005 I was asked to move away for work and Sen and his family flew out to visit. It was then that we decided we would try to make board games again, but now more as a way to stay connected, even though we were on different sides of the country.

We made about six games that got to a pitchable state when we finally decided to take the next step and try to find a way to get them published. We didn’t know anything and in 2008, there weren’t any guides online for how to pitch or even where to pitch games. I ended up going to the GAMA Retail show in Vegas by myself and pitched all 6 of our games. They each had interest from at least one publisher, but ultimately none of them were signed. Undeterred, I went back the next year with some new games, and that’s where our first game, Belfort was signed!

EL: Glad to see the persistence paid off! Can you share your experience during your first ever pitch at the GAMA Retail show in 2008? Were you nervous? Tell us a little more about your preparation and what went through your head if you could recall. We have quite a large audience of budding designers here, so this can help them better prepare for their first ever pitch!

JC: Before I went to GAMA I had no idea what to expect. That said, my day job was organizing nationwide training events for a large retailer, so I knew what a tradeshow was like. I thought it might be a good idea if I had some sort of one-pager that summarized each of the games that I was pitching. We hadn’t heard of anyone else doing this before. It just seemed like a good thing to do. Also, I will point out that I didn’t contact any publisher in advance at all. I didn’t know that I could or that I should! I went there with no leads, no contacts, no info and just winged it!

When I got to GAMA, my first goal was to get a lay of the land. I walked around the entire exhibit floor and ‘studied’ each booth. I saw what kind of games they were selling and which of our games they might prefer. When it was time for my second lap, I created ‘packages’ of my one-pages (soon to be known in the industry as sales sheets or sell sheets). I put the sales sheets in an order that I thought made sense for each publisher. I would hover outside a booth (out of range so it didn’t look like I was creepy!) and when I saw that there was no one at their booth (this was a GAMA event in 2008, so it wasn’t as packed as a GenCon is nowadays), I approached.

I would introduce myself and ask if they were open to seeing any submissions while they were here. This is where I would get a variety of responses:

1) No – we don’t do that.

2) Yes – but it’s not me. Here’s that person’s business card.

3) Yes – what do you have?

4) Yes – let’s book a time when I can leave the booth so you can show me

When I started to pitch (when the answer was 3 or 4), I would bring out my sales sheets and I could instantly see the publishers shift from nonplussed to somewhat interested. I think the sales sheet made it look like I knew what I was doing, or that at least I was serious about game design. I would review anywhere from 1 to all 6 games with each publisher that I managed to find time with and I was able to find interest in each of the 6 games that I had brought to pitch. They were all subsequently rejected, but it didn’t lessen the excitement I felt when a publisher said that they were ‘interested’ in one of our games!

EL: Sounds like you had a really fruitful convention even though you went in cold! Was there a point in time you really wanted to give up after meeting so many rejections or did the rejections serve as a motivation for you to do better in the future? Tell us a little about how you iterate your designs to ensure a higher chance of success in your pitch?

JC: I never wanted to give up! With game design I always have 4-8 games on the go at various stages, so while those 6 were being assessed (and eventually rejected), we were still working on other designs. In fact, the next year I went back to GAMA, and wouldn’t you know it, that’s where I got my first game signed!

Iterating is what you’ll be spending most of the time doing as a game designer. I iterate based on feedback from my playtesters. Is the game providing the experience that I’m going after? Sometimes it isn’t and it might actually become a totally different game (which is great), but sometimes we can’t figure it out and we shelve it for months, years or forever, based on when we have time to revisit with new eyes. So while I’m always thinking about the kinds of things that publishers want (as I want to make commercially successful games as much as I want to make critically successful games), I don’t iterate any differently in preparation of a pitch.

I do prepare for a pitch though. I have learned that you only have a finite amount of time with a publisher during a pitch. That could be as short as 5 minutes or as long as an hour if you’re really lucky. That said, if you have multiple games that you want to pitch, you have to use your time wisely. I always start by saying that I have a few games I’d like to show them, and I’ll give them a 15 second pitch using the sales sheets. I’ll ask them after I quickly pitch all of them that they can then ask more questions about any that they find interesting. I have also learned to not assume a publisher wouldn’t be interested in a type of game based on what they’ve published so far (I once said to a publisher as I was going through my sales sheets, “this one wouldn’t interest you…”, to which they said, “well, show us anyways.” They ended up signing that game!

I also ensure that I have all the prototypes with me and ready to go. Ready to go means that everything is as quick to set up as possible for a pitch. This is way different than packing a game up that’s ready to be played. I don’t want to sit there opening 14 ziplock bags because each resource has its own baggie! Instead, I’ll throw a sampling of the resources into one bag, and combine player tokens in another. I might even seed the deck so that I have the cards at the top to demonstrate the key aspects of the game better.

Another thing I’ll do is I’ll cut the demo short. I don’t have time to get into every nuance of each game, so I’ll wrap up one pitch by saying that there’s more to it with this and with that, but that’s the gist of the game. I’ll ask if they have more questions or if they’d like to see the next game I have to pitch. This often works best and publishers also appreciate a designer who doesn’t waste their time!

If they don’t have time to test the game fully with me, then I’ll ask where their interest lies. Which game or games would they like to take back and playtest with their group? If they are interested in a game, I might ask if I can come back later as I probably have more pitches to do. 100% of the time they’ve been ok with this so far. They get it. They know that I’m out there showing my game off to everyone. If they do take a game, I’ll ask for some sort of time commitment on when they’ll likely get back to me. I’ll also try to avoid exclusivity. I don’t want to give a publisher exclusivity unless they’re actually paying me money. There are exceptions of course, when you really want to partner with a specific publisher and they’re asking for an exclusive look at your game. When this happens I need them to tell me how long they need (never more than 3 months) and I’ll then message them within a week or so of that time elapsing and remind them. If I have other publishers that are interested, I’ll let them know that I’m now starting to send it out again. Sometimes that motivates some publishers into action!

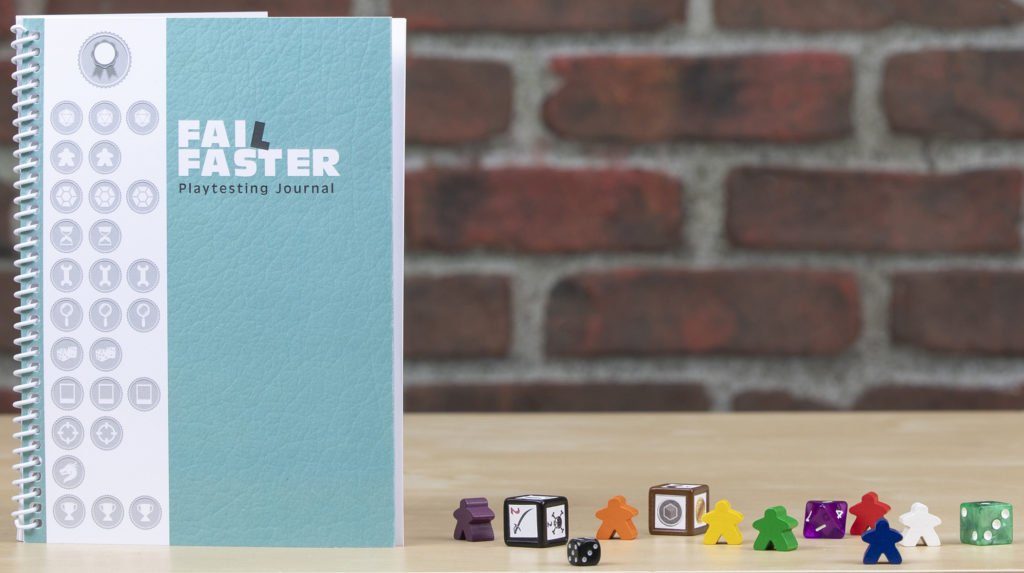

EL: That is great insight on the whole pitching process. I am sure it will greatly benefit designers out there who are looking to pitch their designs at a convention (after the pandemic). How did you go from designing tabletop games to kickstarting a playtesting journal? Is this a side venture or are you steering away from designing games altogether?

JC: I’m definitely not slowing down on game design! 🙂 The journal came about when I wanted to hold a big playtest event 2 weeks before I would pitch these games at a big convention. It also coincided with my birthday, so I made it a birthday/playtest event called JayCon. I rented out a common room in my brother-in-law’s condo and organized the food, and I even brought some of my published games to give away as prizes. But then I wondered if I should have some sort of goody bag — you know, the kind kids get when they leave a birthday party. I started to wonder what would be in the goody bag, and was thinking of putting random components and meeples in there. This then made me think of a mini-notepad to keep track of your notes during a playtest.

From there, this idea kept growing. I really started to think about all the things I’d want to track during a playtest and kept refining it. I scrapped the rest of the goody bag idea and focused on the journal. I got it printed at a local Staples and handed one out to each designer that attended. The feedback was phenomenal! Designers that didn’t make it would come up to me weeks later asking if they could also get one of those journals. Designers that did get one asked me for another one once theirs was completed. It was from their response that I thought there might be a life to this idea outside of my playtest group!

I decided to give it a try and take it to Kickstarter to see if there was interest. I considered my first journal the alpha, and got a lot of feedback from these designers on how to improve it even more. I hired a graphic designer to make the entire thing look professional. It was through this designer’s work that I got the idea for the badges. I had asked for the front cover to look like it was for board game designers, and I provided him with a lot of potential images that he could use. He ended up putting them all in a column down the left side of the cover. It reminded me of boy scout badges! This led me to think that maybe I could gamify this journal. I listed out the top behaviours that I believed if you followed, would make you a better playtester. I then had my graphic designer make badges for each one and I created the page where people would shade in sections until they got to a badge. I thought it would be cool if these were stickers, but now the cost was getting very high, so I thought I’d put that as a stretch goal on the Kickstarter campaign. If we didn’t reach that goal, then the idea is that you would colour that badge in on the cover. Fortunately, we did reach that stretch goal and the journal now comes standard with stickers!!

EL: It’s always great to see a product that is so handy and well-designed come to fruition through crowdfunding! Before we end off, what advice do you have for budding designers out there?

JC: Thanks Ethan! In order to be a successful board game designer you have to become your own MVP. You have to stay Motivated, be Versatile and have Positive Persistence. Being creative means you’re going to have ebbs and flows of motivation. Find ways to stay motivated – whether that’s working with a partner, working on multiple game ideas at a time or by taking a break from it. Whatever you need to do to keep your motivation going. If your goal is to get a game published, then you’ll have to be versatile and make many games in many genres and for different target audiences. If your goal is to get THIS game published, then I hope you’re going to self-publish, as it might take you a looooong time to get a publisher to sign it. Finally, being a designer means you’re going to get a lot of rejection. That’s ok and that’s good. Expect it and grow from it. If they provide feedback on why they don’t want it – great! Use that information to either change your game to better suit them, or come up with a new game that will fit more with what they’re looking for. Be positive about it and stick to it.